Why the Whale Tales?

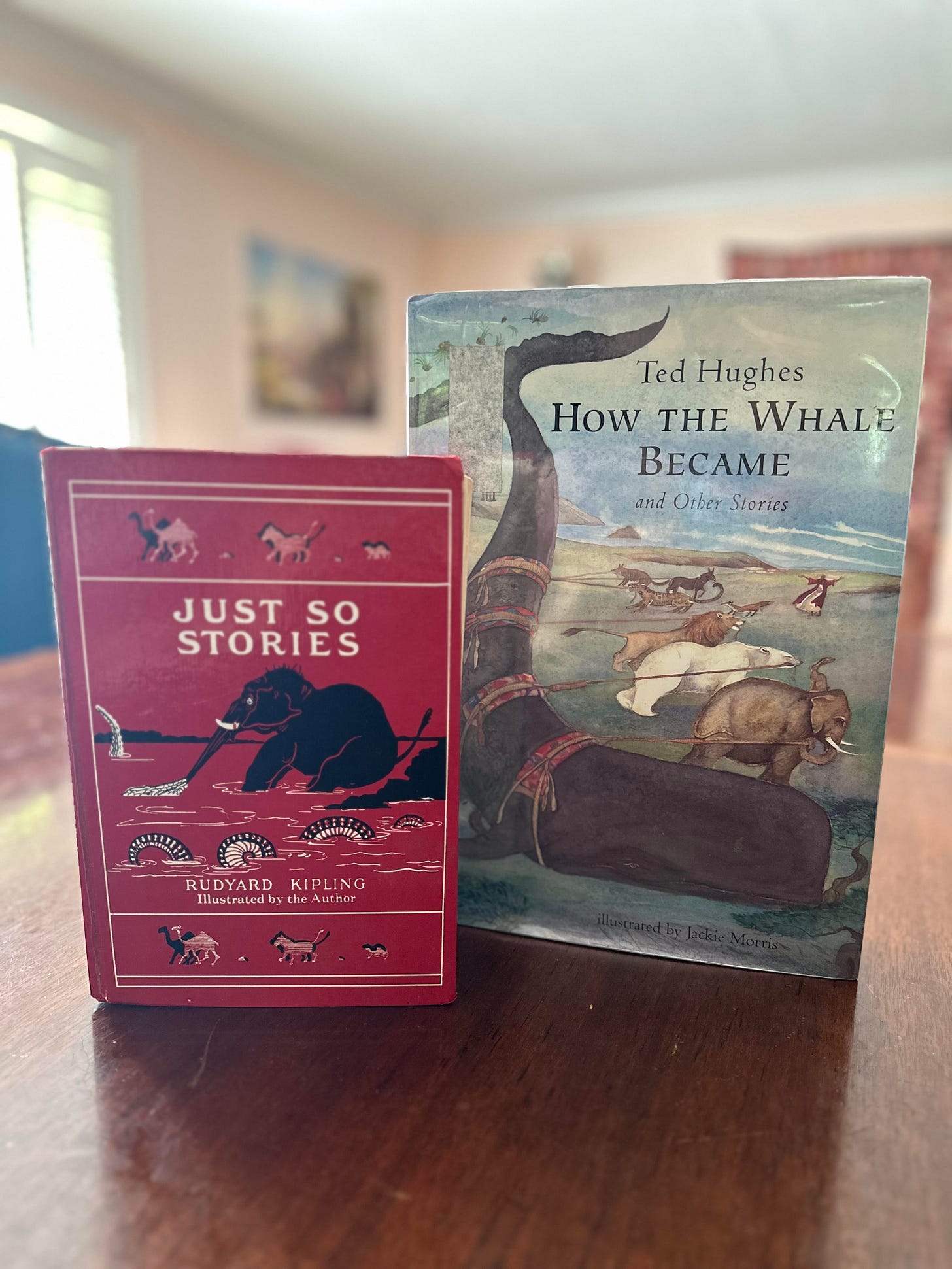

Right beside Aesop’s fables and D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths on my bookshelf, you’ll find creation stories: Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories and How the Whale Became by Ted Hughes, illustrated by Jackie Morris1. Creation stories are a genre – they take place in the early days of creaturely life, where animals and humans roam the nascent earth but have not quite reached their recognizable state. The worlds of these stories share elements of both myth and fable, and they teem with imaginative whimsy and wit. In them, creatures are still developing – coming into their own unique characteristics and quirks – sometimes helped along or punished by various genies or demigods, sometimes internally driven to discover their role in the world, or other times cajoled by their fellow creatures to do something productive. These books offer delightful reading and prove fruitful as they form our imaginations and help us grow in virtue.

So how could borderline-absurd stories of camels and leopards help cultivate such promising fruit?

The first of the various ways I will mention is in the vein of natural history or scientific inquiry. In these tales, we encounter truths about the creatures – we learn how they interact with one another and how they behave in their own right – and this occurs in a storied way, rather than in a dry, factual way. For instance, in the title story of Ted Hughes’ collection, “How the Whale Became,” the whale begins as a garden fruit, whalewort, that grows and grows. He grows so large, he seems likely to cave in the walls of the god’s2 house and subsume the space of his entire garden. Rather than letting this happen, the god rolls him off the edge of a near cliff, into the sea, and declares that the whalewort cannot return to land until he has shrunk. The god pokes a hole in the top of whalewort, who spends his days thereafter blowing as much of himself from the hole in his head as he possibly can manage, trying to shrink enough to return to the motionless ease of his nascent garden. This story provides an entertaining commentary on the spouting mannerisms of the whale, and in this tale and many others, the reader will likely find himself or herself freshly appreciating various aspects of creaturely life – like the way a whale breaches and blows. A book of facts about whales would be interesting in its own right if it were well written; yet, engaging with whales in story doesn’t just inform us, it form us; we learn the habits of the whale while hardly realizing it, in the midst of wondering about the process of growth, the limits of the world, and the actions of each character. And in interactions with whales thereafter, in the literary world or in our wider world, we can greet this creature as a friend, one with whom we’ve shared an experience and gotten to know through these pages.

Kipling’s Just So Stories also open with a story about a whale. In “How the Whale Got his Throat,” Rudyard Kipling plays with the fact that the largest of creatures, whales, eat the smallest of creatures. Whales don’t eat humans, and the reason points all the way back to a clever fish who points the hungry whale toward consuming a man, and a clever man who takes matters into his own hands (you can’t forget his suspenders - you’ll see why when you read). In this story, this kernel of natural knowledge about whales’ diets is more the pretext than the “point” of the tale. The pointiest thing in the story belongs to the man, and it is his wit, even more than his jack-knife. The character’s wit helps us appreciate the wit of the author, and the scintillating intelligence behind these stories is quite the point of pleasure. Kipling wields words, playing with them, bouncing them off one another, and passing them back and forth. Refrains recur again and again, and as you listen to or read these stories, you can’t help stealing away to exotic places, loving his lilting language, and scoffing at the spot-on absurdities of Kipling’s settings and scenes. The way Rudyard Kipling uses language is a reason in itself to engage with these tales.

Anthropological and geographical insights are other benefits to reading these works. Later in his Just So Stories, Kipling paints funny pictures of the beginning of written language, the start of recorded history, the ebb and flow of the tides, and the pitfalls of marriage told through a fantastical version of King Solomon’s historic court. The natural history knowledge on offer in reading these tales is surprisingly rich. Kipling manages to use ridiculous situations to discuss the beginnings of written language and other momentous human developments in surprisingly accurate ways that adults and children can both appreciate and engage with. Geographically, there are many places mentioned that provide context for the stories and for history on a broader scale – particularly if you find them on a map.

A deeper reason to read these books is the nature of the stories themselves – stories of becoming. Every human is engaged in a process of becoming. Each day gives play to our virtues and vices, and the choices we make define our being. Stories of becoming deal in archetypes, making the patterns of personhood clearer to us. We can’t help but glimpse ourselves and people we know in the proclivities of the dreamer donkey, the prideful dandy hare, the sly fox, and the too-cool cat. The interplay of interactions amongst the creatures and humans in the tales determines how each creature comes to be. The vivid details of their stories involve the disapproval or influence of others; in the weave of becoming, these outside influences provide the warp for the weft of each animal’s actions. Reading about them, we subtly recognize that we, too, shrink or grow by how we respond to our place and our relationships. Like the animals depicted, we can poignantly experience shame, discomfort, confidence, or honor. We can seek to escape like Ted Hughes’ Polar Bear, or we can work for rescue and restoration like the Elephant. Becoming doesn’t happen in a vacuum or on an island – it is always determined by our fellows and the fates we face.

The final reason for making these books a part of your experience centers around the imaginatively rich situations and settings of these stories, and the way they grow our imaginations. Bringing us to these settings at the genesis and nexus of development places us in a field that is richly imaginatively fertile. Our imagination is one of our greatest gifts as persons, the means whereby we make connections between all we have seen and heard and taken in. These stories are an imaginative boon. The Just So Stories have been described as a stylistic rollick, “express[ing] the child’s special awareness of the peculiar and extravagant.”3 Phrases such as “Best Beloved” and “infinite resource and sagacity” are shining pearls that the reader will carry with them couched in the soil of their souls. The more our imaginations are expanded, the larger our capacity to recognize the potential for grandeur, beauty, and delight in our world. These stories are directly connected to the tales and stories that have formed the Western imagination. Ted Hughes’ stories read similar to fables, presenting moral situations that pick up tropes that have been handed down through generations. Those same characteristics of Fox we see in Aesop’s Fables and in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales are on display here, and the cat with his violin is a direct homage to Mother Goose and the nursery rhyme. As we see these characters and characteristics again and again in various contexts, images in our imaginations become richer and more vibrant, building out a cohesive frame for engaging with the world around us.

The more we connect with these stories and the truth that stands behind them, the more fruitful they become. Both Ted Hughes and Rudyard Kipling delight in drawing us in so that they can send us out with a fresh eye for the beauty and nuance of creation and the creatures around us, both man and animals. In creating their fictional worlds, both authors help us understand the most fundamental aspects of our world – the partnerships between man and beast, the ever-present pitfalls of pride, and the worthiness of a noble heart. Connecting with these stories connects us with our own stories of becoming, and gives us worthy companions along the way.

Of the many versions of this book that have appeared since it was first published in England in 1963, I mention the one that Jackie Morris illustrated specifically because of the soft, vibrant beauty of her paintings and the wise yet whimsical quality of the animals and their settings.

Ted Hughes calls this character “God”, but I prefer to read it aloud as “the god” in each place the name is used. I think of the deity in Hughes’ collection akin with the gods of myth like Ares of Mars, or “the jin” in Kipling’s Just So Stories. The god in these stories does not act in keeping with the Trinitarian God, and I find that this substitution helps my kids and I keep from muddying the clear distinctions between the gods of myth and the God of the Christian faith.

Elizabeth R. Choi, Forward to the 1978 Edition of Just So Stories by Rudyard Kipling, Crown Publishers, Inc: Weathervane Books, 1978.